The extract from The Prelude that we will read in class is, as the title suggests, part of a longer autobiographical poem (of the same name) which begins in 1798 and, amongst other things, describes Wordsworth’s time in France before and during that most momentous of events – the French Revolution. Wordsworth re-wrote and revised the poem but it wasn’t published until much later (in fact, just after his death).

The extract from The Prelude that we will read in class is, as the title suggests, part of a longer autobiographical poem (of the same name) which begins in 1798 and, amongst other things, describes Wordsworth’s time in France before and during that most momentous of events – the French Revolution. Wordsworth re-wrote and revised the poem but it wasn’t published until much later (in fact, just after his death).

Spots of Time and The Sublime

To understand this poem, it’s worth considering two things that characterised Wordsworth’s style and philosophical ideas. One of these was his idea about ‘spots of time’. These were dramatic moments in life which burned themselves into his memory. He talks about these earlier in The Prelude:

There are in our existence spots of time,

That with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence–depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight,

In trivial occupations, and the round

Of ordinary intercourse–our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired;

A virtue, by which pleasure is enhanced,

That penetrates, enables us to mount,

When high, more high, and lifts us up when fallen.

These spots of time are moments in life when an experience might be described as spiritual or magical. This is not to say they are religious or supernatural, but they are special, rare, powerful: the memory of them fills our being, and we remember each moment vividly. I’m sure you’ve all got your own experiences. For Wordsworth, these spots of time were mostly inspired by his encounters with nature and this leads us on to the second key concept when trying to understand this section of The Prelude – the sublime.

The sublime, says the British Library, is an aesthetic (artistic and creative) concept which “revolved around the relationship between human beings and the grand or terrifying aspects of nature” (see below for reference). The Romantic poets were obsessed with idea and one of the best poems to express this idea for me is Shelley’s Mont Blanc in which he talks about the terrifying beauty of the mountain. The sublime in its simplest terms (and this is simple because there are post-graduate classes in the sublime which still struggle to tie it down) is that moment when something powerful, huge perhaps even terrifying, fills the senses and can become overwhelming. It might induce feelings of fear, awe and wonder. Again, the Romantics linked this to the landscape – great mountains, dizzying precipices, vast cataracts etc. Think of standing over the edge of a cliff: that feeling of vertigo might be part of a sublime experience – feeling the lure of the abyss. This feeling of the sublime is one described in Wordsworth’s poem. Can you think where?

The Prelude

We will begin by looking at two paintings from the Romantic era:

The one on the left is Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea and Fog. Romantic artists tried to capture the sublime experience through their paintings and in this one the figure on top of the precipice is above the clouds. In a way, you could argue that this is the Romantic idea of humans mastering nature – he is looking down on the world and has overcome the fear of nature (although he should have taken a hat).

Now look at the image on the right. This is Avalanche in the Alps painted by Philip James de Loutherbourg. Look how terrified the figures in the landscape are – and how small they are. Nature – the mountains – are overwhelming, filling the frame (reminds me of the clashing mountains in the first Hobbit film). Here, nature is terrifying in its size and threatens to engulf the minuscule figures in the frame. These two images, for me, are effective in expressing the ideas of the sublime but also, in their contrasting perspectives, help us understand the ways in which Wordsworth’s feelings change in this part of the poem.

So now let’s look at The Prelude in two parts:

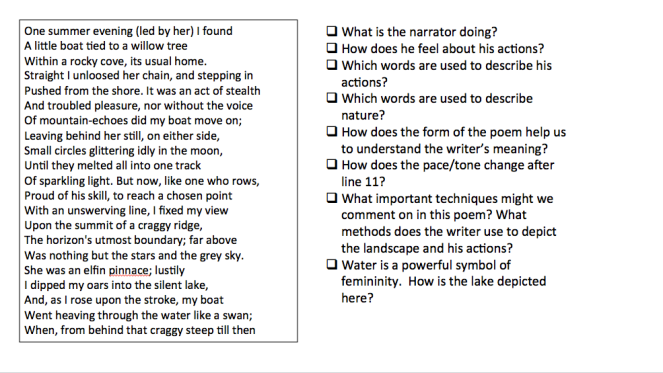

The young Wordsworth steals/borrows a boat to go sailing on Ullswater in the Lake District. The area around Ullswater consists of rugged landscapes that would offer Wordsworth a great opportunity to express the sublime experience that follows. The verbs ‘unloosed’, ‘stepping in’ are less dynamic, more hesitant perhaps and this is reinforced by Wordsworth calling this ‘an act of stealth’. However, the key phrase next is ‘troubled pleasure’ which suggests there is some excitement in the danger of taking a small boat out on the lake at night. The silence of the landscape suggests a watchfulness, as if the mountains around him are observing this act of transgression but there is also a magical quality to the setting – ‘small circles glittering idly in the moon’, ‘sparkling light’ etc.

Question: does Wordsworth feel this ‘troubled pleasure’ at the time of the incident or is this upon reflection? Spots of time…

As the young poet rows his boat further away from shore, there is a change in tone. Subtle at first – ‘But now’… From here, the poet is more determined: he fixes his view on the summit beyond, apprehensive perhaps of losing sight of his destination. He comments on the void above ‘nothing but the stars…’. He is aware of the fragility of his boat – ‘an elfin pinnace’ (small, and here gendered female). Now look at the way he describes his propulsion of the boat. The verbs and adverbs become more aggressive and active – ‘lustily’, ‘dipped’, ‘rose upon the stroke’, heaving through the water’. Water is often a symbol of femininity, so what might be happening here?

The second part of this extract is identified by the change in tone – the volta – and thus begins Wordsworth’s sublime experience. He had not noticed the ‘huge peak’ before, but now it comes into view. The sublime experience occurs with the shock of new encounters (will I feel as queasy the second time I go to the top of the Eiffel Tower perhaps?) and look how he describes this first sighting:

The second part of this extract is identified by the change in tone – the volta – and thus begins Wordsworth’s sublime experience. He had not noticed the ‘huge peak’ before, but now it comes into view. The sublime experience occurs with the shock of new encounters (will I feel as queasy the second time I go to the top of the Eiffel Tower perhaps?) and look how he describes this first sighting:

a huge peak, black and huge,/As if with voluntary power instinct,/Upreared its head.

The repetition of ‘huge’, so close together, is obviously not Wordsworth’s lack of a range of vocabulary, so why do you think he does this? Has he become utterly gob-smacked by the sight? Rendered bereft of words? He personifies the peak – it ‘upreared its head’ like some fantastic beast of mythical legend. It is almost gothic in its appearance – a ‘grim shape’ which ‘towered’ up and blocks out the starlight. It’s a wonderful evocation of the way in which nature blocks out the imagination, fills our very beings with awe and terror. And look at the verbs that Wordsworth uses to describe his movement through the water – “struck and struck again”, “trembling oars”. The sight of the mountain has instilled a real fear into the narrator, increasing his own violent energies (if the lake is female…). But the mountain continues to move ‘with a purpose of its own’ and appears to pursue Wordsworth who is now struck with terror. He goes back to his starting point and leaves his boat, although this might not be the only thing he leaves there: his innocence, his supper, perhaps?

The final section of the poem is Wordsworth reflecting on the experience – linking this to his idea of ‘spots of time’. He can’t fathom the experience – it is still sublime: ‘a dim and undetermined sense of unknown modes of being’ and it hangs over his thoughts like ‘a darkness’. At the end of the poem, Wordsworth expresses the terror of the experience in language that evokes the gothic: this shadowy spectacle that lurks on the edges of his consciousness could just as well be an evocation of Fuseli’s Nightmare

The experience has left a lasting effect on Wordsworth, fusing itself into his memory. He dwells on it, it has become a ‘spot of time’. But perhaps there is more and these two images again are worth returning to:

Wordsworth began by attempting to conquer nature, to master it (like the first painting). The way he steals the boat and the language used to describe the way he rows out on to the lake all suggest this attempt to submit nature to his own will – “lustily, I dipped my oars into the the silent lake”. The lake is passive and he is active, and he is dominating its serenity with his invasion. He is ‘proud’, ‘unswerving’ – it is the language of arrogance. However, this arrogance is soon stopped by the appearance of the mountain – a phallic presence which seems to rise as a figure of vengeance and chase the invader away (see the second painting). The end of the poem is therefore Wordsworth’s fear of the unknown but also an understanding that nature cannot be tamed and that, like the monster of our nightmares, is a sublime presence that lies in wake to teach us powerful lessons.

Ironically, the sublime exceeded the imagination which is why poets tried to capture it in words and yet perhaps here at the end Wordsworth’s language of the gothic and the numinous suggests that words ultimately cannot express the experience adequately.

References:

Thank you for this. It’s wonderful. You capture the mood and express the undertones of the poem beautifully. Much appreciated. Sarah

LikeLike

Thank you Sarah.

LikeLike

Thank you. So helpful and clear. Your blog was recommended at my last AQA hub meeting by the way

LikeLike

Absolutely fabulous. Superb analysis and linking with the images

LikeLike

I found the paintings really helpful in explaining the power of nature. Thanks.

LikeLike